What is ensiling silage?

Ensiling is the process of storing a forage crop to preserve it. There are four phases associated with ensiling:

- Initial aerobic (oxygen present) phase

This begins immediately after the forage crop has been cut and continues during the initial period after ensiling. It is not helpful because sugars in the forage are wasted as a result of respiration by the forage plant itself and by microorganisms living on the plant. Sugars are broken down and lost into the atmosphere as CO2, with heat produced in the process. Proteins are also wasted as they are broken down by the plant and by microorganisms. Therefore, the shorter this phase, the better. - Fermentation phase

When all the oxygen in the clamp or bale has been used up and conditions become anaerobic (no oxygen present) the main fermentation occurs. For the reasons mentioned above, ideally this is brought about by lactic acid-producing bacteria, which may be naturally present on the crop or added by applying a suitable additive. The goal is that this phase proceeds as rapidly and efficiently as possible, so that the growth of undesirable and wasteful microorganisms is quickly halted. - Storage (stable) phase

This occurs once the fermentation is complete and can last a few weeks or several years. During this phase there will be minimal microbial activity and the silage should remain more-or-less stable, provided the clamp remains properly sealed. - Feed-out phase

When the clamp or bale is opened for feeding and the silage is exposed to air again, this allows aerobic microorganisms, such as yeasts and moulds, to become very active again, leading to dry matter and nutrient losses.

The history of silage

The word silo comes from the Greek word 'siros' which means a hole or pit in the ground for storing corn. It is known that the Greeks and Egyptians were familiar with ensiling as a technique for storing fodder as far back as 1000 to 1500 BC. In parts of Northern Europe grass was being ensiled in the early 18th century but it was not until the latter part of the 19th century that it became more widespread.

The first book on silage was published by a French farmer, based on his experiences with green maize. He advised rapid filling of the silo and stressed the importance of keeping it air-tight during storage. A year later an English translation was published in the USA and American farmers quickly adopted the new technique. Although the French and American farmers were very enthusiastic, it was not until 1882 that a talk given at the Reading Show of the Royal Agricultural Society stimulated interest in Britain. By 1886 there were apparently 1,605 silos in the country, with farmers here concentrating on ensiling grass rather than maize.

Unfortunately, silage making in the UK suffered a set-back in 1885 when a book was published recommending that silage should best be made by heating it initially to at least 50°C by aerating it. Although the silage produced was palatable it was of very poor nutritional value and losses were very high. Nevertheless, the method persisted until the middle of the last century.

The 1970s and 80s saw a dramatic shift from conserving grass as highly weather-dependent hay to the more flexible system of producing grass silage. The introduction of big bale silage brought the additional benefits of transportation plus flexibility with storage and feeding.

What is the science behind silage-making?

Grass silage is basically pickled grass. The aim is to retain as much feed value as possible – which is done by encouraging lactic acid bacteria to ferment grass sugar to produce desirable lactic acid.

The lactic acid lowers the pH and prevents the growth of spoilage microorganisms, allowing a stable preservation. To achieve this, there must be sufficient sugar available, fermentation must occur as quickly as possible and air must be excluded throughout (anaerobic conditions).

This can be done in a silage clamp or in big bales. Both have the same objectives:

- Rapid removal of air (through consolidation or compaction)

- Rapid fermentation of grass sugars to lactic acid

- Maintenance of anaerobic conditions in the clamp/bale during storage

Caption: Effective consolidation to remove air from the clamp is crucial for good silage

Getting the right microbial population is essential to make good silage. High numbers of the right kind of lactic acid bacteria (LAB) are needed for a fast, efficient fermentation. These will outcompete less desirable bacteria that waste sugars by fermenting them to weaker acids, e.g. acetic acid, or non-acid alcohols. A fast fermentation to a low, stable pH will also prevent other undesirable bacteria from growing (e.g. a clostridial fermentation).

Several growing and harvesting factors will also influence forage and silage quality, for example:

Growing

- When reseeding, select the variety which meets your requirements for harvest date, yield, quality, soil type and climate

- Follow good crop management practices to encourage yields without reducing sugars

- Avoid late application of fertiliser

- Try not to surface-apply slurry within 10 weeks of mowing (and preferably not at all) as it introduces undesirable microorganisms

- Injecting slurry can be done up to two weeks from harvest

Wilting

- Wilt rapidly (24 hours maximum) to about 30% dry matter if conditions permit to concentrate sugars and reduce effluent. Shorter wilting times also help to reduce in-field losses that occur due to crop and microbial respiration. Longer wilting leads to greater loss of valuable nutrients and proliferation of spoilage organisms

- As a guideline, 1% of moisture is lost per hour of sunlight in bright conditions. It can be greater with mower-conditioners and tedding

What are the most important factors influencing grass silage quality?

- The grass type and variety

- Grass sugar content

- Fertiliser

- Stage of growth at cutting

- Percentage dry matter at ensiling

- Chop length

- Contamination (e.g. from slurry bacteria)

- Additive use

- Speed of ensiling

- Exposure to air

- Feeding technique

Is it possible to have quantity and quality with grass silage?

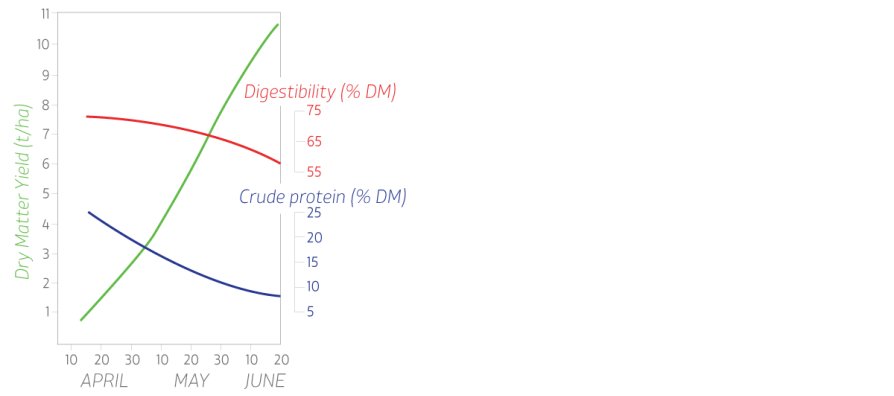

In a normal year the optimum date for cutting is usually a compromise between the quantity (yield) of that cut and its quality.

This occurs because as grass develops its fibre content increases and the degree of lignification increases leading to a reduction in digestibility. The digestibility (D value) falls about 0.5% per day after heading. Protein concentration also falls, further reducing feed value.

However, it is possible to get around this to some degree – by cutting grass younger and more often – e.g. in a multi-cut approach. By using this method, although individual cuts may be lighter compared with cutting less frequently, in Volac trial work, grass from a five-cut system had an average digestibility 3 D units higher and was almost 3% higher in crude protein than grass cut three times. Furthermore, over the season, the five-cut system also yielded 0.92 t/ha more total dry matter.

When do I need to stop grazing grass silage fields?

Over-wintering cattle can induce poaching on medium to heavy soils, producing a rough surface and increasing the likelihood of soil contamination when mowing. Grazing by sheep, on the other hand, can be beneficial, as it removes stemmy and dead grass leading to more digestible silage.

Ideally stock should be removed before any spring growth appears. Failure to remove them by the end of January will reduce first-cut yields and also increase the risk of contamination with manure. If intending to spring graze, stock should be taken off by the end of March, although this may need adjusting depending on when first-cut will be taken.