Treating grass silage with an additive

Is an additive needed when making grass silage?

With the silage in a clamp potentially worth tens of thousands of pounds, it is well worth protecting it by ensuring a good fermentation.

Whenever grass is ensiled, some sort of fermentation will occur. The problem is that some fermentations are poor ones – resulting in much more of the silage’s dry matter (DM) and nutrient content being lost. Other fermentations are much more efficient.

The quality of the fermentation will be influenced by various factors – e.g. by maximising the sugar content of the grass by cutting at the optimum growth stage and achieving a rapid wilt; by minimising contamination with soil or slurry bacteria; and by ensuring the clamp is well consolidated and airtight. But another integral step is to use a proven additive that ‘bombards’ the clamp with a high number of efficient bacteria which rapidly produce lactic acid. Ecosyl, for example, drives fermentation by delivering 1 million, highly efficient Lactiplantibacillus plantarum MTD/1 lactic acid-producing bacteria per gram of forage treated. Lactic acid, in turn, ‘pickles’ the forage to preserve it.

Without the additive, fermentation is at the mercy of whatever bacteria happen to be present on the grass – both good and bad bacteria. Bad ones may come from soil or slurry, but even if slurry and soil bacteria are minimised, the lactic acid bacteria that tend to be naturally present on grass are often low in number and not necessarily the most efficient strains. If the wrong bacteria dominate the initial fermentation the pH will fall slowly, which will allow undesirable microorganisms to continue ‘feeding’ on the ensiled grass for longer, leading to greater silage losses.

Some silage additives have even been shown to bring about improved animal performance, even when the untreated silage would have fermented well anyway.

Compared with the value of silage, the cost of treating with Ecosyl is minimal.

Caption: Each gram of grass (pictured) receives 1 million highly efficient fermentation bacteria on average when Ecosyl is applied

What happens when silage is made with a quality additive?

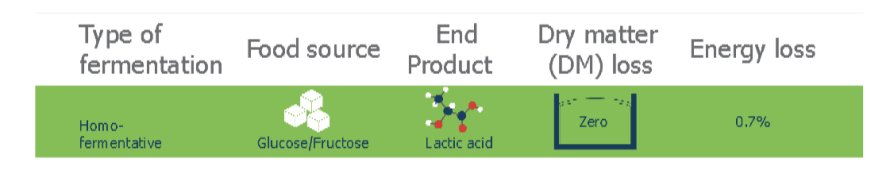

In an ideal fermentation, only lactic acid is produced. This is highly beneficial for two reasons:

- No undesirable by-products are produced during this process, which means very little energy is wasted. Indeed, the lactic acid produced retains over 99% of the energy of the original fermented sugar

- Lactic is the strongest acid produced during a silage fermentation, so it produces the fastest pH fall – from about pH 6 in the fresh forage to around pH 3.8-4.5 (depending on the crop and % dry matter in the final silage). In this way, the growth of undesirable microorganisms is quickly halted before they have chance to cause major nutrient losses

It is this type of fermentation that occurs when a quality silage additive containing a high number of efficient lactic acid-producing bacteria (e.g. Ecosyl) is applied. It is called homofermentative because there is only one end product: lactic acid.

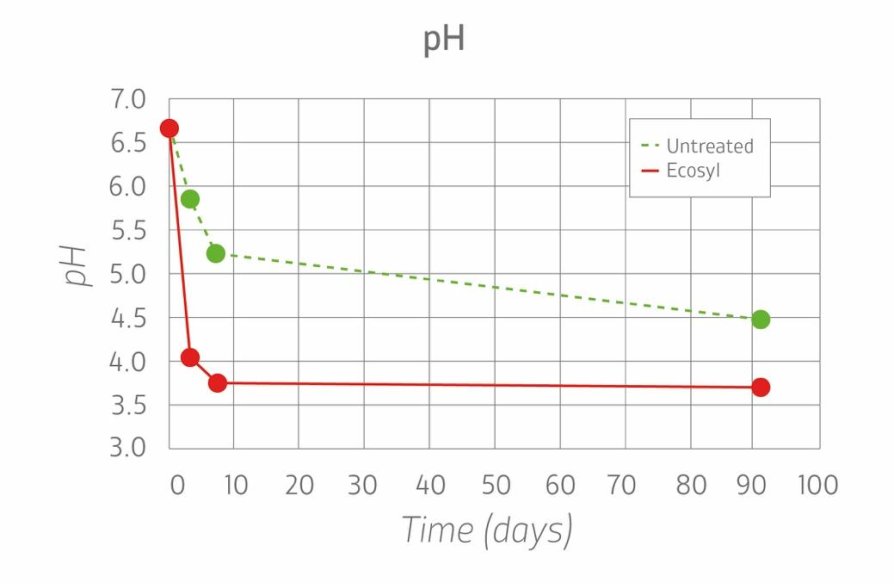

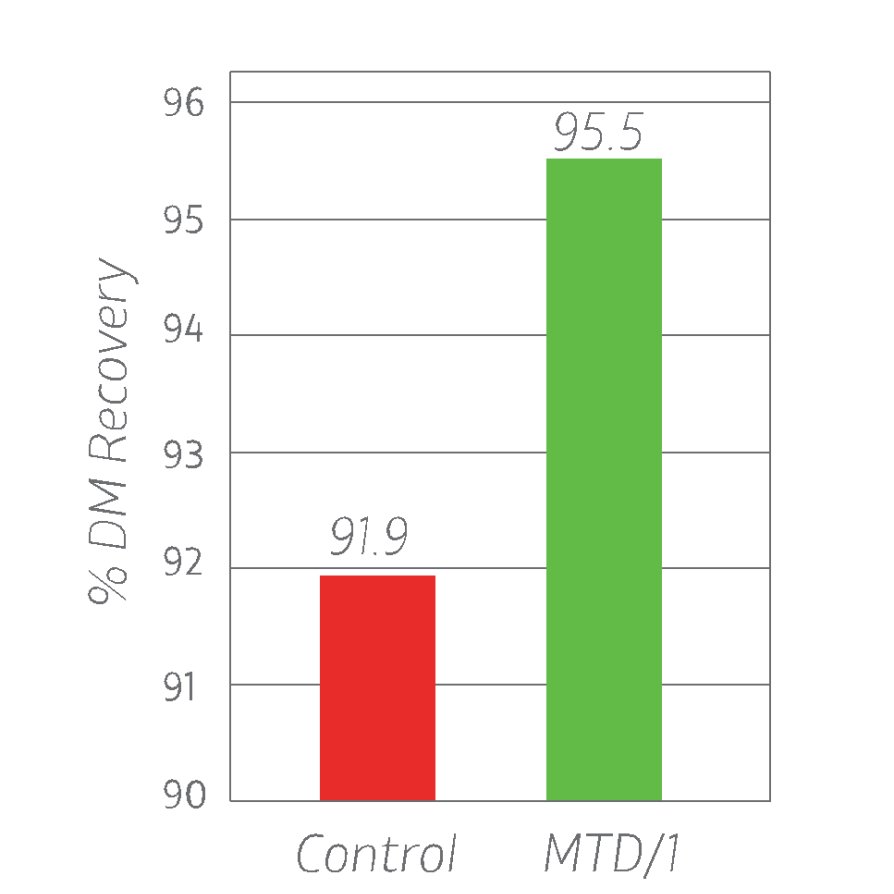

Research on Ecosyl has shown that it not only produces much faster pH falls than an untreated fermentation (see chart below) but it has also halved dry matter (DM) loss and conserved greater nutritional quality.

In trials, using Ecosyl has been shown to boost silage metabolisable energy by 0.6 MJ/kgDM compared with untreated silage, and to improve animal DM intakes. It has also preserved more true protein. Most important of all, Ecosyl has led to improved animal performance. Across a range of forages in 15 international independent trials, milk yield from feeding silage made with Ecosyl was improved by an average of an extra 1.2 litres per cow per day over untreated silage.

An ideal fermentation produces beneficial lactic acid and preserves more of the original energy of the sugar

Silage fermentation results in DM and energy losses. How big these are depends on the end products of fermentation. The best silage fermentation is when sugars are fermented only to lactic acid, as with MTD/1 in Ecosyl. (See later for the higher energy losses from less efficient fermentations.)

Speed of pH fall in untreated silage and silage preserved with a proven additive (Ecosyl)

Improved dry matter recovery in silage preserved with Lactiplantibacillus plantarum MTD/1 (as in Ecosyl)

How important is a fast pH fall and low pH in grass silage?

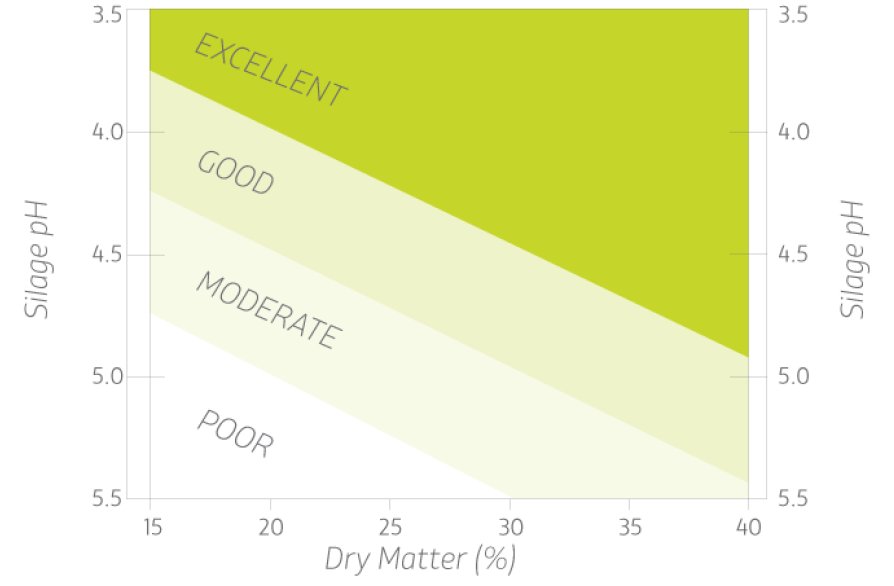

With all silages it is important that the pH comes down quickly, and to a level low enough to stabilise the silage.

The faster the pH value falls, the sooner the wasteful activities of the live plant material and undesirable microorganisms will stop. This reduces losses, conserves more sugars and reduces protein breakdown for example into ammonia.

With the Ecosyl silage additive, research has shown a much faster production of beneficial acidic conditions in the first 24 hours after ensiling with the treatment than without.

If the pH is slow to fall and/or sugars run out before a stable pH is reached, undesirable bacteria such as clostridia can take over as they can convert lactic acid to butyric acid, a much weaker acid, so the pH increases again (clostridial secondary fermentation).

The wetter the ensiled crop, the lower the final pH needs to fall in order to stabilise the fermentation.

Effect of pH on silage preservation quality at different % dry matters

Can a silage additive be seen working?

Unfortunately, it can’t. At least, not easily.

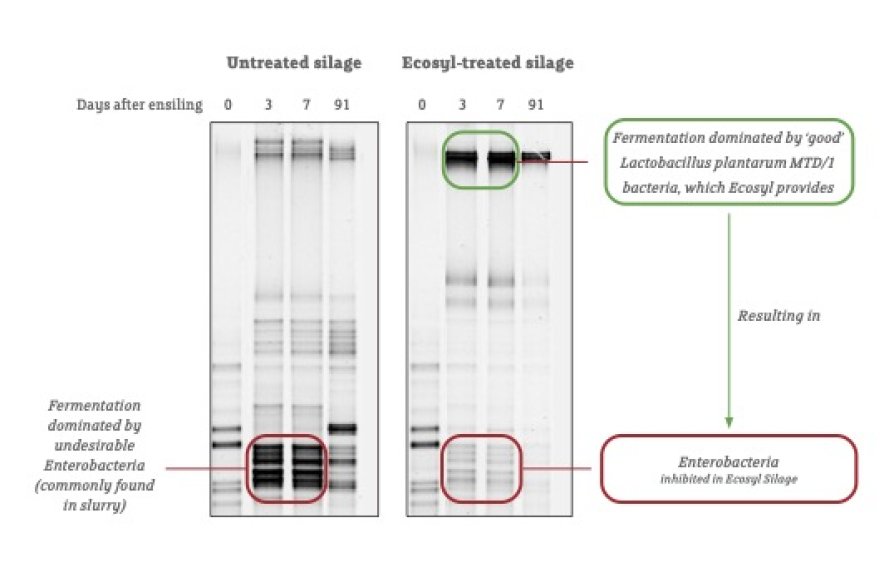

However, to provide an insight into the workings of an additive, Volac scientists have used DNA fingerprinting to reveal the different bacteria present in silage (in this case, multi-cut) – both with and without Ecosyl applied – at 0, 3, 7 and 91 days after ensiling.

DNA fingerprinting is a technique used in forensics. Here it is used to produce an image (see picture below) where horizontal bands represent the DNA of different bacteria. Darker banding indicates more of that bacteria is present.

Where no additive was applied (left), results revealed that during the early part of the fermentation in particular, the silage was dominated by undesirable enterobacteria, commonly found in slurry.

Where Ecosyl was used (right), there was very little growth of enterobacteria, as the ‘good’ bacteria present in Ecosyl dominated the fermentation. The result was that the undesirable bacteria were inhibited from growing.

DNA fingerprinting reveals how ‘good’ bacteria in Ecosyl outcompete undesirable bacteria

What happens if grass silage ferments poorly?

What happens if grass silage ferments poorly?

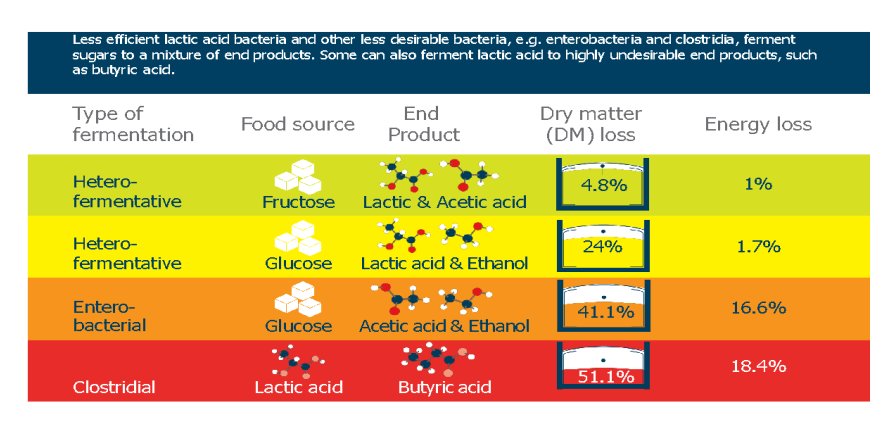

At the opposite end of the scale to an efficient fermentation, poorer fermentations can occur for two reasons. Firstly, if they are carried out by bacteria naturally present on the grass that still produce lactic acid but do so less efficiently. Or secondly, if certain ‘bad’ bacteria are present on the grass.

The issue with these bad bacteria is that they produce a range of less desirable end products besides lactic acid. This type of fermentation is termed heterofermentative.

These end products can include other acids called volatile fatty acids (VFAs). VFAs are weaker than lactic acid, which means the pickling process is slower and the pH may not fall as low, so undesirable microbes can continue feeding on the valuable nutrients in the silage for longer. On top of this, carbon dioxide is produced. This is particularly undesirable because carbon dioxide means loss of dry matter and is not good for the environment. Another by-product of a poor fermentation is ethanol, which is not a preservation acid at all.

Particularly poor fermentations occur if enterobacteria, the bacteria associated with slurry, are present on the grass and allowed to persist in the clamp, or if clostridia bacteria are present, which are introduced from soil. These can waste around 17 and 18% of the original energy content of the sugar.

Clostridial fermentations are particularly undesirable because they convert beneficial lactic acid into much less desirable butyric acid, which makes silage unpalatable. So not only is the silage less nutritious, but livestock want to eat less of it.

The slower fall in pH during the early stage of fermentation also means that there will be a greater breakdown of proteins, mainly due to continued plant enzyme activity.

Good silages should have a suitable pH of 3.8 - 4.5 depending on the % dry matter, low ammonia-N (less than 10% total N) and a high ratio of lactic acid to volatile fatty acids – a minimum of 3:1 or higher.

Less efficient types of fermentation and their dry matter and energy losses

Less efficient lactic acid bacteria and other less desirable bacteria, e.g. enterobacteria and clostridia, ferment sugars to a mixture of end products. Some can also ferment lactic acid to highly undesirable end products, such as butyric acid.

How can a silage additive influence silage quality?

Using an additive can lead to a silage of higher nutritional quality than untreated silage by reducing the losses of more digestible nutrients.

Across 18 animal feeding studies, average metabolisable energy was increased by 0.6 MJ/kgDM with Ecosyl treatment.

In addition, Ecosyl has been shown to preserve more true protein.

Research on Ecosyl has shown it to not only reduce dry matter loss but also conserve greater nutritional quality in silage