Baled grass silage

What are the advantages and disadvantages of baled grass silage?

Advantages:

- Low capital investment – for the potential to carry out the whole operation in-house (so fields can be cut according to optimum growth stage, rather than contractor availability)

- Potentially lower labour requirement than clamped silage

- Flexible harvest – e.g. for clearing overwintered grass ahead of the main first-cut clamped silage or odd fields outside of the main clamp silage window

- Flexible feed-out

- Quality can be as good as (or even better than) clamped silage

- Low storage costs

- Low pollution risk

- Can sell surplus

Disadvantages:

- More expensive to make than clamped silage

- Susceptible to risks from moulding, mycotoxins and listeria – particularly at higher % dry matters

- Unsuitable for low % dry matter grass

- More variability

- Prone to damage

- Labour/time at feed-out

- Plastic disposal

Why should I consider making grass silage in bales?

Originally bales tended to be one way of avoiding having to invest capital in a new clamp. They were also useful if wanting to make a bit more silage when the clamp was full.

Now, improvements in baling and wrapping equipment mean baled silage can be every bit as good as clamped silage and, because of potentially lower losses, may cost less too. This makes bales a first option for some farms rather than something to fall back on. Having some bales of first-cut also removes the need to open the clamp early for autumn calvers.

Making big bale silage in place of hay also has advantages. For example, it simplifies and improves sward management; the same seed mixture and fertiliser regime can be used for all of the conservation area – both clamped and baled grass. It can also increase the total dry matter that can be produced per hectare compared with hay, as more productive, earlier heading varieties can be used.

How does the feed quality of bales compare with clamped silage?

There is no reason why baled silage should be inferior to clamp silage if grass of equal quality is ensiled. In fact, the quality potential of baled silage can actually exceed clamped silage if the farm has its own machinery, since the grass can be cut at its nutritional optimum rather than being reliant on contractor availability.

The proviso is that good practice must be adopted when making bales, rather than viewing bales as a second class forage. Bales are essentially mini clamps, so use the same attention to detail as with clamped silage. Avoid using older, lignified grass and use best-practice conservation to preserve nutrients.

Many modern balers make it easier to produce tightly-wrapped bales from one machine, reducing the amount of air that is potentially trapped in the bale.

What are the golden rules for making baled grass silage?

- Wilt rapidly to the target % dry matter

- Rake up to form box swaths of uniform width and density

- Make dense, well-shaped bales

- Net to the edge (or over) so no soft air traps

- Wrap within 2 hours

- Use a good quality wrap

- Consider using a lighter colour of wrap

- Use enough layers of wrap

- Do not leave bales in the field

- Handle gently and as little as possible after wrapping

Is Listeria a problem with baled grass silage?

The bacterium Listeria monocytogenes is found in soil and slurry as well as in small numbers on grass. It infects sheep and cattle causing listeriosis which leads to abortions and encephalitis. Sheep are more susceptible to infection because differences in their teeth make it easier for the bacteria to access the nerves.

Listeriosis has increased significantly in sheep since the introduction of big bale silage. With cattle, infection of the eye by Listeria causes “silage eye” a painful ulceration which is treatable. This happens because the animal tends to push its head into the more palatable centre of the bale and this may allow infected grass stalks to poke it in the eye. It is obviously less of a problem with chopped bales.

Listeria can survive in low numbers in silage but will not multiply as long as air is excluded and the pH remains below about pH 5. In the presence of air, however, it can survive at much lower pH values. If a lot of air gets in, yeasts will grow causing the pH value to increase and providing ideal conditions once again for Listeria to grow and multiply. Bales can therefore benefit greatly from an additive that will improve fermentation and reduce aerobic spoilage.

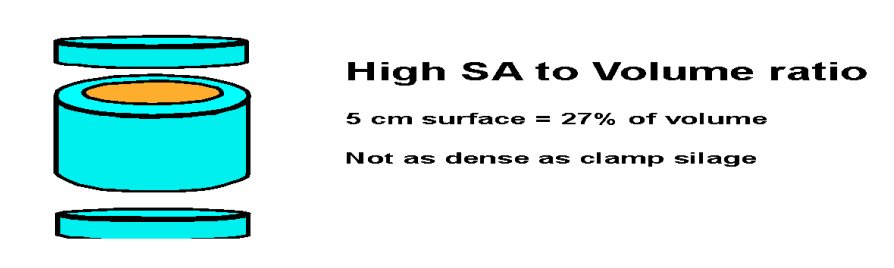

Listeria is more likely to survive and grow in big bale silage than clamp silage. This is the result of a number of factors. The low density and high % dry matter content often associated with baled silage results in a slower, less extensive fermentation. In addition, bales have a very high surface area to volume ratio, exposing more of the silage to air if the wrap becomes damaged. Listeria growth is usually associated with the outer layers of bales where the bacteria can be present in very high numbers, especially if the silage is visibly mouldy.

Do grass swards need to be managed differently for baled silage?

No, manage them to produce top-quality forage, as with any other silage. It is important to always use good quality grass for bales as coarser grass will not consolidate so well, trapping more air and hence being more likely to suffer from moulding.

Why is it important to wilt grass for baled silage?

Wilting is essential when making bales for the following reasons:

- Better fermentation

- Lighter weight bales

- Fewer bales per hectare to cart and store

- In order to prevent effluent leakage

- It leads to more solid, better-shaped bales that wrap and stack better

- Drier bales retain their shape better – deformed bales can let air in

How can baled silage be improved?

Paying as much attention to detail making baled silage as making clamped silage as a key starting point. In particular, cutting grass at its optimum timing before heading, rather than leaving it until later and cutting older grass as often the case with bales.

Typically, 35-45% dry matter (DM) is considered optimum for baled grass silage. However, although these higher %DMs may be appropriate for beef and sheep, dairy farmers should not be afraid to make bales slightly wetter (e.g. 30-35% DM) for several reasons.

These include: to reduce wilting times and therefore in-field nutritional losses and to make it easier to produce finished bales in catchy weather; as well as to improve the fermentation and reduce the risk of losses from heating and spoilage associated with drier silage.

Bales have a large surface area for air to penetrate, so sealing as soon as possible also helps to reduce risks of losses from heating and spoilage. Modern balers that produce finished, tightly-wrapped bales in one machine reduce the opportunity for air to penetrate.

In addition, consider the use of a quality additive [LINK TO NEXT SECTION] to improve dry matter and nutrient retention. Also, store and stack bales correctly to avoid damage and splitting.

Bales have a large surface area to volume ratio.